Black August – Los Angeles is in our famous works category as a result of its role in shaping the artistic digital legacy of Black August. From its inclusion in Wikimedia’s Black Cultural Archives to its widespread use as an educational resource, this artwork ensures the history and symbolism of Black August remain accessible for generations to come.

Black August, now known as the Black History Month Alternative for freedom fighters, has a rich history rooted in the struggle for justice and equality, marked by remembrance and activism.

Origins of Black August: The Spark at San Quentin State Prison

In 1979, Black August was initiated by African American inmates at San Quentin State Prison, marking a significant period of remembrance and resistance. This observance was sparked by the death of Khatari Gaulden, a Black inmate who died on August 1, 1978, due to state-sanctioned medical neglect at San Quentin. Rather than solely commemorating Gaulden’s death alongside those of other activists like W.L. Nolen, Alvin Miller, Cleveland Edwards, and George and Jonathan Jackson, the prisoners chose to dedicate the entire month to honor their struggle against the expansive prison-industrial complex in California.

The decade leading up to the establishment of Black August witnessed a series of deadly encounters initiated by state officials within California’s prison system. On January 13, 1970, a confrontation between Black and white prisoners at Soledad Prison led to the death of W.L. Nolen, Alvin Miller, and Cleveland Edwards, who were fatally shot by a prison guard. These incidents ignited a series of retaliatory actions, including the murder of a Soledad Prison guard, for which George Jackson and two others, now known as the Soledad Brothers were implicated. Over the next 19 months, 19 murders within the California prison system were directly connected to these initial deaths.

A pivotal moment occurred on August 7, 1970, when 17-year-old Jonathan Jackson, George Jackson’s younger brother, was killed during an armed takeover of the Marin County Courthouse. In an attempt to negotiate the release of the Soledad Brothers, Jonathan Jackson armed himself and took several hostages, resulting in a fatal shootout that also claimed the lives of Judge Harold Haley and two inmates, while severely injuring a prosecutor and a juror. The firearms used by Jackson were traced back to Angela Davis, a political activist who was later acquitted of related charges.

In 1970, George Jackson’s notoriety soared with the release of the book Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson. His letters provided an authentic critique of systemic racism in America, particularly within the prison system.

On August 21, 1971, Jackson was murdered by prison guards at San Quentin State Prison during an alleged escape attempt in which Jackson was purported to have been in possession of a gun. Three prison guards and two inmates were killed. Mrs. Georgia Jackson, the mother of George Jackson, said that her son had been murdered and his body dragged outside by guards.

While the 1970, state-sanctioned murders of Nolen, Miller, and Edward sparked widespread carnage throughout the California prison system, the state-sanctioned murders of George Jackson had national repercussions. The day after Jackson’s death, in New York, at least 700 Attica prisoners participated in a hunger strike in his honor.

Attica’s non-violent hunger strike would bleed into a full blown riot in September. The Attica Prison Riot, September 9 – 13, 1971, had become, at the time, the greatest loss of life from clashes between prison guards and prison inmates in the history of the United States. Forty-three people, thirty-three prisoners and 10 prison officials, either guards or staff were killed. The uprising at Attica had marked a significant moment in the prisoners’ rights movement.

Black August is now observed annually to honor those who fought for Black liberation, advocate for the release of political prisoners, denounce the conditions within U.S. prisons, and highlight the ongoing struggle for freedom. Participants engage in a month of reflection, discipline, and action, including fasting, physical training, political study, and activism, embodying the principles of study, fast, train, and fight.

These principals would organically lead into a much deeper examination of Black freedom struggles during the month of August.

– Haitian Revolution: On August 22, 1791, the Haitian Revolution began with a slave uprising in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, eventually leading to the creation of the first Black republic.

– March on Washington: On August 28, 1963, civil rights leaders gathered for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.

– Watts’s Riots: On August 12, 1965, in Los Angeles, California

– Assassination of George Jackson: On August 21, 1971, during a prison riot at San Quentin. Mrs. Georgia Jackson, the mother of George Jackson, said that her son had been murdered inside the Adjustment Center, and his body dragged outside by guards.

– The death of San Quentin prisoner Khatari Gaulden: On August 1, 1978, Khatari Gaulden, was left to die, as a result of medical neglect by San Quentin Prison authorities.

– Black August started in 1979: Instead of adding Aug. 1 (Gaulden’s death), to the existing days of observation that marked the deaths of activists like W.L. Nolen, Alvin Miller, Cleveland Edwards, and George and Jonathan Jackson, the prisoners standing in resistance to the massive California prison-industrial complex declared the whole month to be Black August.

– Hurricane Katrina: On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana, causing devastating damage and disproportionately affecting Black communities.

– Shooting death of Michael Brown: On August 9, 2014, unarmed Black teen Michael Brown was shot to death by a Ferguson, Missouri, police officer. Brown’s body was left on the summer pavement for 4 hours, and sparked the international outcry, “Hands Up! Don’t Shoot!”

– Fatal plot against Hugo “Yogi” Pinell: On August 12, 2015, Soledad Six member, aka Soledad Brothers’ member, Hugo “Yogi” Pinell was shanked to death by white prisoners after being released from solitary confinement, as a result of a federal court order ending the practice of long-term solitary confinement in the California prison system.

Over the years, Black August has gained international recognition as a time to acknowledge the ongoing struggle for justice and to honor those who have fought for civil rights and prison reform.

Black August – Los Angeles: The Artwork

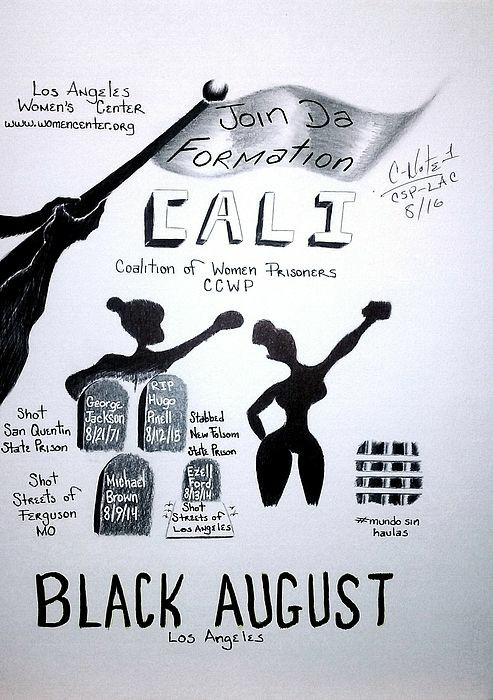

Created in 2016, Black August – Los Angeles is an ink on paper artwork by Donald “C-Note” Hooker, known as the world’s most prolific prisoner-artist. This piece marked C-Note’s first foray into political art.

The artwork was inspired by a Facebook Page of the same name, in which the page owner Jitu Sadiki (1956 – 2023), was informing the public about the accompanying Black August Los Angeles Calendar Page, and all the Black August events that were going to be taking place in Los Angeles.

The artwork epitomizes C-Note’s artistic prowess as a strong flagbearer for women.

The arms of a very muscular man are holding a flag pole, and waving a flag with the words, “Join Da Formation.” It is a reference to Beyonce’s highly controversial record, Formation. Right below the flag are the block graffiti letters “CALI,” a street vernacular reference to the State of California, which is connected to the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP), below it.

In the upper left hand corner, C-Note creates a space to acknowledge and bring awareness too, the Los Angeles Women’s Center, a respite for women coming home from prison, or in circumstances that lead to prison. He goes beyond merely providing the name of the facility, but provides the website URL for donation purposes.

The lower half of the composition has clear reminders of the initial rationale behind Black August, prison deaths. It features tombstone references to the deaths of Soledad Brothers, George Jackson in 1971, and Hugo “Yogi” Pinell, who in 2015, who was shanked by white prisoners, shortly after Pinell was released into the general prison population after California ended long-term solitary confinement.

There is also a tombstone and headstone reference to the state-sanctioned murders of two unarmed young African American males. Hovering over the tombstones are women with their raised fists, formerly a symbol of Black power, but now represents solidarity with any movement struggle. On the right of the lower half of the composition is prison bars with the words, “#mundo sin jaulas,” which translates, “A world without cages,” in recognition of the Brown People’s Movement.

In 2017, Black August – Los Angeles was donated to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, specifically to Sister Mary Hodges of the Partnership of Reentry Program (PREP), for a joint art exhibition with Homeboy Industries. This gesture highlighted the artwork’s significance in the context of restorative justice and community healing.

The artwork is listed in Wikimedia Commons’s Black Cultural Archives, underscoring its importance in the documentation and celebration of Black culture and history.

Black August – Los Angeles not only commemorates a pivotal moment in the struggle for justice but also serves as a powerful reminder of the ongoing fight for equality, the importance of remembering those who have been lost, and the need for systemic change.

Own a Piece of History with “Black August – Los Angeles” Art Prints

Black August – Los Angeles transcends traditional wall art, embodying a rich narrative of struggle, resilience, and the fight for justice. This iconic artwork, pivotal in the digital legacy of Black August, offers a unique opportunity to connect with history.

Purchasing a print means embracing a legacy that honors the spirit of Black August, ensuring its profound symbolism remains accessible. It’s not just art—it’s a reminder of the ongoing battle for equality and the power of solidarity.

Support the cause and honor the memory of those who fought for freedom. Your purchase contributes to initiatives focused on restorative justice and community healing.

Seize the chance to own a piece of history. Buy a Black August – Los Angeles print today and stand with those who continue to fight for justice and equality – click on the image below 👇